- Home

- Darren Shan

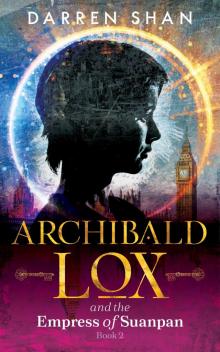

Archibald Lox and the Empress of Suanpan

Archibald Lox and the Empress of Suanpan Read online

ARCHIBALD LOX

and

THE EMPRESS OF SUANPAN

BY

DARREN SHAN

Archibald Lox, Volume One, Book Two of Three

ONE — THE CLOCK

1

I wander the streets of New York, enjoying the sensation of being in a new city, on a different continent. I think back over everything that has happened since I spotted Inez on the bridge, and while I’m sad that I have to leave that strange, magical other world, I’m delighted that I got to experience as much as I did.

I’d love to explore. There are lots of places I want to see, Central Park, the High Line, the Brooklyn Bridge, the Statue of Liberty, but time is pressing and it would be wrong to act like a tourist when Inez is in danger.

I decide to head straight to the Empire State Building, and stop to ask someone for directions, which is when I remember that they can’t see or hear me.

I scowl, wondering what to do. I could look for a map, but that’s an ordinary solution to the problem, and I don’t want to do this the ordinary way. I want to taste a bit more weirdness before the adventure is over.

I spot a man wearing a sandwich board and handing out leaflets, trying to drive people to a local restaurant. I walk up behind him, then say in a hushed voice, “You want to go to the Empire State Building. You need to go to the Empire State Building right now. You…”

I stop when the man turns to look at me.

“What’s your problem?” he growls.

I gawp at him.

“You trying to pull some dumb trick?” he barks.

I gulp and try a shaky smile. “Sorry. I got lost. I’m supposed to meet my dad in front of the Empire State Building. I meant to ask you to please show me the way, but I guess it came out wrong.”

“It sure did,” the man huffs, but his expression mellows. “You want me to call a cop, kid?”

“No, that’s OK,” I say quickly.

“You sure? New York’s a dangerous place for a boy on his own.”

“I’m not on my own,” I lie. “I’m with my mum and dad. Mum’s off shopping – Macy’s, I think – but Dad’s waiting for me. Our hotel is close to Times Square. He gave me a map, with the route marked, but I dropped it.”

“Where you from?” the man asks.

“London.”

“London, England?”

“Yes.”

“You English are a funny lot,” he laughs. “I wouldn’t let no kid of mine off by himself in a strange city, map or no map. But I guess that’s how you guys conquered the world, huh? Fearless explorers.”

I smile politely.

“It’s not far anyway,” the man says. “This is 36th and 9th. Carry on down to 34th.” He points me in the right direction. “Swing a left and keep going till you get to 5th. Turn right and you’re there.”

“Great,” I beam. “Thanks for your help.”

“Hey, that’s what our special relationship is all about, right?”

I’ve no idea what that means, but I nod and say, “Right.”

“Hey,” he stops me as I start to walk past, “can you do me a favour in return?”

“What?” I ask warily.

“Can you take one of these?” he says, passing me a leaflet. “Twenty percent off if you wanna come here later with your old man.”

2

I follow the man’s directions to the Empire State Building. It takes about a quarter of an hour, then I’m standing in front of the main entrance. It would be cool to go inside and get a lift to the top, but I don’t want to waste time, so I look for the yellow, spire-topped borehole.

I find it to one side of the doors, in the window of a pharmacy. It’s like it’s been built into the glass. I step through, expecting to wind up in the Merge, but to my consternation I find myself inside the pharmacy. There’s a wide vine ahead of me, but shelves stacked with tubes and bottles all around, and lots of people shopping.

“What the hell?” I grunt.

Nobody jumps or looks at me. It seems like I’m invisible again.

The vine is unlike any I’ve seen before. It’s as if the top half has been crunched down into the lower half, giving the vine the appearance of a long, U-shaped tube, a bit like a curved water slide. It starts in the middle of the aisle and slopes upwards, cutting through a shelf of vitamins. As I watch, a woman reaches for a box of pills. Her hand passes through the vine, her fingers close around the box, and she lifts it off the shelf.

“This is too weird,” I mutter. Vines in the Merge are one thing, but vines in the Born, running through shelves, are another thing entirely.

I step forward – a woman and her child automatically edge out of my way – and reach for the vine. My hands don’t pass through it. Instead my fingers tighten on the two sides and I step on. I look up and see the vine climbing into the ceiling. I’ve a sneaky feeling that the ceiling isn’t as solid as it seems.

I haul myself along. I probably don’t need to use my hands – it’s not that steep – but I’m not going to let go until I’m sure of my footing.

As I’m crawling upwards, one of the men who works in the store moves beneath me. He bends to avoid my legs, almost doubling over, but his head passes through the vine. I can’t understand how the vine is mist-like for them but firm for me.

“It’s just a Merge thing,” I tell myself, trying to sound like Inez would if she was here. “Space is different, yada yada.”

I smile. I might not be able to understand this, but that doesn’t mean I can’t enjoy it. Warming to the task, I crawl forward another few metres, stopping when my forehead comes to a rest just below the ceiling.

I push my left hand up and my fingers disappear into the panels, as I thought they would. I leave them there a moment, then pull my hand back and flex my fingers — they’re all present and correct. “Of course they are,” I snort, then push through the ceiling of the pharmacy and carry on up.

The vine twists its way upwards through offices, corridors, toilets (I close my eyes), cupboards and more. It winds forwards and backwards, all over the building.

At one point it pokes through a wall and I find myself outside. I’m high off the ground – I must be thirty or forty storeys up – so I hunch over, afraid the wind will rip me loose. Then I frown. There isn’t any wind. Instead there’s a lifelessness to the air that’s familiar from my time in the Merge.

I wish Inez was here to explain this, but she isn’t, so I just carry on as the vine leads me back into the building and through more rooms and offices. The vine cuts through walls, floors, desks, chairs, pipes, toilet seats. It can overlap just about anything, and while I’m on it, I overlap those objects too, my limbs sliding through solids as if they were made of fog.

Thirty or forty floors later, the vine slices through a wall and I’m outside again, looking over the city. It’s a spectacular sight, but it’s not the view of New York that makes me freeze and hold my breath.

It’s the view of the other cities.

Impossibly, I’m not just looking at the Manhattan skyline. Dotted in among the local skyscrapers are landmarks from other countries, such as the Eiffel Tower, the Taj Mahal, the Kremlin.

I turn in a daze and there’s the Sydney Opera House standing close to an ancient Egyptian pyramid. The Tower of Pisa is leaning off to my left. More pyramids on my right, but these look like the ones they have in Mexico. There’s the hill from Rio with the large statue of Christ with his arms outstretched. The huge skyscraper that Dubai is famous for.

There are more, landmarks I recognise and some I don’t, but all alien to the New York setting, connected by

a network of foot vines like the one I’m frozen to.

Weird is one thing. I’ve adjusted to weird over the last couple of days. Me and weird have learnt to get along pretty well.

But this, on my own world, where I thought I would be returning to normal… This is too much for me.

I sit, staring at the fantastical vista like a baby in a pram, no words to express what I’m feeling, just a big ball of vacant, slack-jawed wonder adrift in a universe that hasn’t started to make sense yet.

I forget about time, Inez, the Merge, my mission, everything else. There’s just the deliriously delicious spread of famous buildings that can’t be here but are, and I gaze at them in silent wonder, waiting for my brain to melt.

When it doesn’t, my senses begin to return.

“O,” I wheeze. Then, a while later, I add, “K.”

I push myself to my feet and look around. This is the Merge but also the Born. The spheres are overlapping, the way the vine overlapped with objects in the building. I don’t know how that can be, but it is, so it’s time to quit being dazed and just deal with it.

I focus, looking for the clock tower that Inez mentioned, and spot it immediately. I should have guessed. In a sea of famous landmarks, what’s the most recognisable clock in all the world?

“Big Ben strikes ten,” I sing solemnly, “ding-dong, ding-dong.”

London’s renowned clock tower lies ahead of me in the distance. It looks the same as it did when I was studying it a couple of days ago from the bridge over the Thames, the Houses of Parliament just behind it, the London Eye…

No. I was going to say the London Eye just across the river, but the Eye isn’t part of the landscape. And now that I do a double take, I realise the Houses of Parliament aren’t there either — the clock tower stands alone.

The foot vine stretches out, unsupported by any pillars, snaking through the air. It branches off in lots of places, arms leading towards the global landmarks, bending over and under other vines that lie in its way.

I glance back at the Empire State Building, worried it will disappear if I move away. I have a route back to the Born through this, but if I move on and the passageway to New York vanishes, maybe I’ll be stuck up here forever, lost in the clouds of a most unique wonderland.

No. Inez told me I’d be able to return to the Born after delivering my message, and also that I’d be close to where I lived. There must be another vine like this one, running down Big Ben. George and Rachel are in London, worrying and waiting for me to return, and this unlikeliest of routes is going to deliver me straight to them.

“Come on,” I sigh, taking my first step forward. “Time to go home.”

3

This should be gut-wrenching, walking along a narrow strip of vine so high above the streets – one tumble and I’m history – but I proceed at a calm, steady pace. Maybe it’s the unreality of the situation, but I just don’t sense any danger.

I could take a side-vine – I’ve always wanted to visit the Taj Mahal and Sydney Opera House – but I stay focused on Big Ben. I’m not here to go sightseeing. Inez sent me to deliver a cry for help.

The vines are deserted, which surprises me. I’d have thought a place like this would be teeming with tourists.

It takes a couple of hours to make my way to the tower. When I finally arrive, I find that the vine stops short of the clock face by half a metre. Hanging between the vine and the clock is a round, grey borehole, a couple of metres in diameter.

Recalling Inez’s instructions to shout until someone hears me, I open my mouth.

Then I close it.

I can see a lock in the heart of the borehole, a dark green colour, large enough to accommodate both my hands. Inez told me there was no way I could open this lock. She’s probably right, but I don’t see the harm in trying.

I crack my knuckles and lean forward, slipping my hands into the lock. I find lots of pieces of metal, far more than in the locks in the borehole on the bridge. My first impression is that Inez was right — this lock is too complex to pick. I start to withdraw, then pause.

Inez said it would be a few days before she’d be able to make her rendezvous. And the SubMerged didn’t chase me, so I don’t need to worry about them sneaking up on me. Time’s on my side. Why not play with the lock and see how far I get?

Sliding my fingers forward again, I prod the pieces inside the lock, concentrating hard. For a long while I don’t get anywhere, but then a hazy picture forms, and I get a vague sense of how the lock might work. I press on slowly, teasing the internal workings, not flicking or pressing any part until I’ve explored other parts around it.

This is unbelievably intricate. So many tumblers, levers and pins. I slip into a meditative mood and everything else becomes a blur. A bear could come along and chew off my legs and I wouldn’t notice. I barely blink, my eyes fixed on the point where my hands disappear into the lock.

I must be breathing but I’m unaware of it. The lock is everything. My fingers and thumbs are ten linked explorers, passing information to one another and back to my brain, where a map is slowly being drawn. Sometimes I make a mistake, but I catch it after a few minutes and go back, correct it, try again.

I persevere for hours, and would happily work away at it for hours more, but suddenly the little finger on my right hand rolls a tiny, hidden tumbler, and there’s a soft click. The circular borehole shimmers and turns transparent.

I spy lots of clock parts through the open borehole, and I hear loud ticking noises. It looks like the borehole leads into the clock tower, but surely nobody would put such a complex lock on a borehole just to keep people out of a clock.

Then, as I’m staring into the ticking gloom, a man calls to me. “After all that hard work, it would be a sizeable anticlimax if you didn’t come in, Master Lox.”

I take a step back, alarmed. “Who’s there?” I cry.

“There’s only one way to find out,” the man says, and I sense that he’s smiling. But is it a gentle or a vicious smile?

“Who are you?” I shout, but this time he doesn’t answer.

I look back the way I’ve come and lick my lips. I could retrace my steps to the Empire State Building, but even if I didn’t have a message to deliver, curiosity would urge me onwards.

“One of these days you’re going to let your thirst for new experiences land you in serious trouble,” I growl to myself. “And this could very well be that day.”

But since I do have that thirst, and since I’ve come all this way, and since I’m here on Inez’s business, I draw myself up straight, put on a brave face, and step forward, through the borehole, into the dark, ticking cavern of Big Ben.

TWO — THE LOCKSMITH

4

There’s a soft click – the same as when the lock opened – when I enter the room. Looking back, I see that the borehole has darkened and closed behind me. The lock has reappeared, meaning I’d need to pick it again to reopen the borehole. That means a fast escape is out of the question.

I gulp and edge forward.

I expect the ticking noises to be linked to Big Ben, but they’re not. There’s a light ahead of me, shining through a doorway from another room, and in the glow I see that I’m not in the bell tower, but in a room made of vines. And there are cuckoo clocks everywhere.

I stop and stare at the clocks. There are scores of them, large and small, all set to the same time and ticking in chorus.

“I hope you’re not afraid of cuckoos,” the man says. I still can’t see him.

“I didn’t know that anyone was afraid of cuckoos,” I reply.

“You’d be surprised,” the man chuckles.

“It must be really noisy when the clocks strike the hour,” I note.

“Chaotic,” the man says cheerfully.

I step through into the next room, which is much brighter, and the man is waiting a couple of metres ahead of me, smiling warmly and making the greet, which I return. He

’s elderly, with a head of thick white hair, dressed in dark overalls and a white, stained shirt, with a spotty bow tie. Sandals instead of shoes. His cheeks are lined with an array of ancient scars. They must have leant him a fearsome look years ago, but now they blend in with the wrinkles.

The man slips around me – he moves easily despite his age – and closes the door, muffling the sounds of the clocks.

“Cuckoo clocks were a fad in the Merge a few centuries ago,” the man says. “Devisers competed to create the most Born-like examples. Interest soon faded, but I collected a lot of the clocks and stored them here. I’ve always been a keen amateur horologist. How about you, Master Lox? Does clockwork excite you?”

“No,” I answer, then add, “and I’m not a Lox.”

The old man smiles. “Now that I don’t believe. Nobody but a skilled locksmith could have picked the lock on that borehole. I constructed it, and at the risk of sounding boastful, there aren’t many who can pick one of my locks. If you’re not a Lox, what are you?”

I hesitate, not sure how to answer, then shrug and say, “I’m Archie.”

“Nice to meet you, Archie,” the man says. “My name’s Winston, and as you’ve probably already guessed, I’m a Lox too.”

“I’m really not a Lox,” I say shyly.

“You haven’t trained?” Winston asks.

“No.”

“How peculiar,” he murmurs. “You must be highly talented if you can pick locks by instinct alone.”

I blush. “I just slip in my fingers and twiddle them round.”

Winston grimaces humorously. “In truth, that’s what we all do.”

The elderly locksmith moves across the room and I follow. We step through a doorway into a larger, even brighter room, candles poking out of the ceiling. This is where Winston lives – there’s a bed, a couch, some chairs – but it’s also where he works, as the room is full of tables and benches overflowing with locks.

Ocean of Blood

Ocean of Blood Slawter

Slawter Brothers to the Death

Brothers to the Death Zom-B Clans

Zom-B Clans Zom-B Fugitive

Zom-B Fugitive Demon Thief

Demon Thief Lord of the Shadows

Lord of the Shadows Zom-B Circus

Zom-B Circus Hell's Heroes

Hell's Heroes Bec

Bec Hunters of the Dusk

Hunters of the Dusk The Vampire Prince

The Vampire Prince Trials of Death

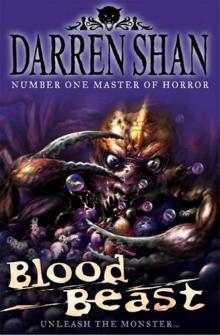

Trials of Death Blood Beast

Blood Beast Koyasan

Koyasan Zom-B Goddess

Zom-B Goddess Wolf Island

Wolf Island Lord Loss

Lord Loss Lady of the Shades

Lady of the Shades Tunnels of Blood

Tunnels of Blood Zom-B Bride

Zom-B Bride Allies of the Night

Allies of the Night Zom-B Baby

Zom-B Baby Deaths Shadow

Deaths Shadow Zom-B Angels

Zom-B Angels Zom-B Mission

Zom-B Mission Dark Calling

Dark Calling First Bites

First Bites Birth of a Killer

Birth of a Killer Archibald Lox and the Bridge Between Worlds

Archibald Lox and the Bridge Between Worlds Archibald Lox and the Vote of Alignment

Archibald Lox and the Vote of Alignment Killers of the Dawn

Killers of the Dawn Vampire Mountain

Vampire Mountain Zom-B Gladiator

Zom-B Gladiator The Vampire's Assistant

The Vampire's Assistant Zom-B Family

Zom-B Family Palace of the Damned

Palace of the Damned A Living Nightmare

A Living Nightmare Brothers to the Death (The Saga of Larten Crepsley)

Brothers to the Death (The Saga of Larten Crepsley) Killers Of The Dawn tsods-9

Killers Of The Dawn tsods-9 Death's Shadow td-7

Death's Shadow td-7 CIRQUE DU FREAK 7 - Hunters of the Dusk

CIRQUE DU FREAK 7 - Hunters of the Dusk Archibald Lox and the Forgotten Crypt

Archibald Lox and the Forgotten Crypt Allies Of The Night tsods-8

Allies Of The Night tsods-8 Hunters Of The Dusk tsods-7

Hunters Of The Dusk tsods-7 Slawter td-3

Slawter td-3 Vampire Prince tsods-6

Vampire Prince tsods-6 Archibald Lox and the Empress of Suanpan

Archibald Lox and the Empress of Suanpan Trials Of Death tsods-5

Trials Of Death tsods-5 Hell's Horizon tct-2

Hell's Horizon tct-2 ZOM-B 11

ZOM-B 11 Cirque Du Freak - Book 1

Cirque Du Freak - Book 1 02 Ocean of Blood tsolc-2

02 Ocean of Blood tsolc-2 Wolf Island td-8

Wolf Island td-8 Tunnels of Blood tsods-3

Tunnels of Blood tsods-3 Cirque du Freak 3 - Tunnels of Blood

Cirque du Freak 3 - Tunnels of Blood 01 Birth of a Killer

01 Birth of a Killer The Vampire's Assistant and Other Tales from the Cirque Du Freak

The Vampire's Assistant and Other Tales from the Cirque Du Freak Hell's Heroes td-10

Hell's Heroes td-10 Zom-B #12

Zom-B #12![[Cirque du Freak 11] - Lord of the Shadows Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/03/31/cirque_du_freak_11_-_lord_of_the_shadows_preview.jpg) [Cirque du Freak 11] - Lord of the Shadows

[Cirque du Freak 11] - Lord of the Shadows Lord Of The Shadows tsods-10

Lord Of The Shadows tsods-10 Demon Apocalypse td-6

Demon Apocalypse td-6 The Saga of Larten Crepsley (3) – Palace of the Damned

The Saga of Larten Crepsley (3) – Palace of the Damned The Vampire's Assistant tsods-2

The Vampire's Assistant tsods-2 City of the Snakes tct-3

City of the Snakes tct-3 02 Ocean of Blood

02 Ocean of Blood Vampire Mountain tsods-4

Vampire Mountain tsods-4 The Lake Of Souls tsods-11

The Lake Of Souls tsods-11 Lord Loss td-1

Lord Loss td-1 Cirque Du Freak Book 6 - Vampire Prince

Cirque Du Freak Book 6 - Vampire Prince Procession of the dead tct-2

Procession of the dead tct-2 Vampire Prince

Vampire Prince Sons Of Destiny tsods-12

Sons Of Destiny tsods-12 Cirque Du Freak tsods-1

Cirque Du Freak tsods-1 Procession of the Dead

Procession of the Dead Dark Calling td-9

Dark Calling td-9 03 City of the Snakes

03 City of the Snakes Blood Beast td-5

Blood Beast td-5 Demon Thief td-2

Demon Thief td-2